Why I Still Opt Out

Cross posted on The Huffington Post

After traveling extensively to film festivals with my film this year, I’ve gotten good at the airport game. A few weeks ago, I arrived at LAX one hour before takeoff, boarding pass already in hand and laden only with the backpack on my back. I faced a nearly empty security line, but felt trepidation.

I handed my ID and boarding pass to a TSA agent. I pulled out my bag of 3 oz or less toiletries and my laptop. I removed my shoes, sweatshirt, wallet, keys, cell phone, belt. When I’m nervous at an airport, I begin to get nervous about being nervous. Whether or not the TSA employees were watching to guess at my psychology, I felt scrutinized.

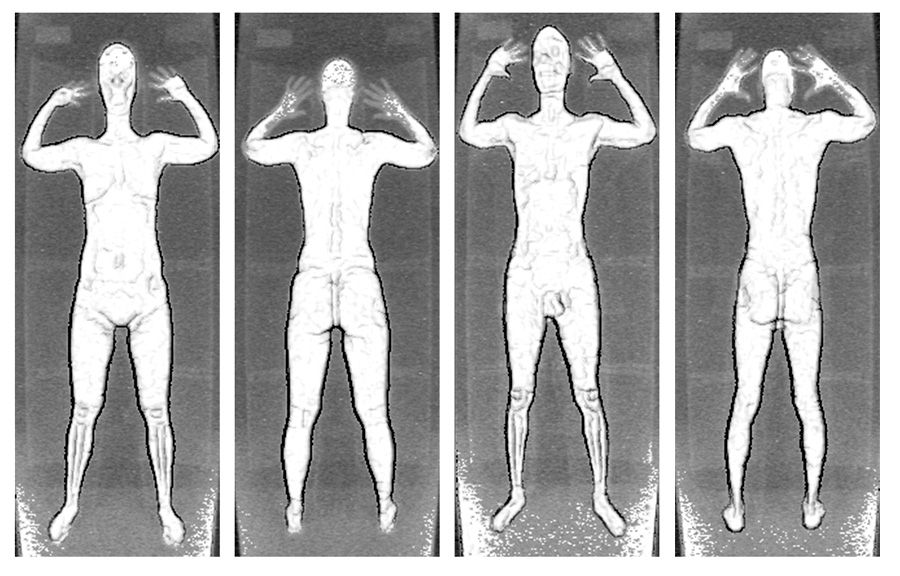

At the front of the line came the moment of truth. I looked ahead. There were two machines — a classic metal detector and a millimeter wave body scanner. The TSA employee was directing people semi-randomly into one machine or the other. I watched the two people ahead of me go into the metal detector and I swallowed. The TSA agent motioned to the body scanner.

“I opt out,” I said, cursing in my head.

“Male opt out!” she yelled, loud enough to be heard several terminals over. Once I opt out, I witness what seems to be a carefully scripted piece of theater. In most cases I am walked through the metal detector, (which doesn’t go off, making me want to yell “look! see! according to your other screening technology I am clean!”), and asked to identify my bags. This time, a nice man gave a particularly detailed description of what he was going to do.

I decided that I didn’t want to do this any more. The thought of the body scanner virtual strip search was abhorrent, but this time I just didn’t want to be groped in public. I asked to go back through the scanner and he told me that once I opted out, returning was not an option.

The search commenced. He ran his fingers inside my waistband and up the inseam of my pants on both sides until he could distinctly feel my genitals. He touched all parts of my chest and back to be sure I wasn’t hiding anything there.

It may have just been this man’s procedure and mannerisms, but this felt different than the cursory exams I’d gotten several years ago when the TSA introduced the body scanners. It felt more invasive. The explicit narration of a stranger’s fingers, followed by an almost chiding reminder that the millimeter technology is totally safe, ratcheted the whole thing to a new notch of offensiveness.

And I remembered why I opt out.

The TSA inspires a culture of fear. The indignities we are made to suffer at airports are a manifestation of a government that does not trust its people, and believes that the way to security is to encourage us not to trust each other. Traveling through a country owned by us, the people, we are asked to present identification at numerous checkpoints as if we have something to prove; we are asked to strip down and be observed as if we are suspects.

I don’t say the word “bomb” at an airport. There are no jokes about bombs at an airport. I don’t laugh when I’m at the police checkpoints dotting our country. We fear our policemen for what they might do to us. We’re afraid to film them. When I send texts that might sound like terrorist threats, I add a joking disclaimer afterwards because I think — no, I am certain — that my communications are being monitored by a computer for signs of suspicious activity. If I must be frank, I’m a bit nervous about publishing this article.

That this elaborate stageplay of airport security has been shown to be ineffective adds further offense.

And so the government official touching me to be sure that yes, that is indeed my penis and not a weapon, keeps me grounded in awareness that I am not happy with this current state. Rather than standing in the body scanner and lifting up my hands (in a literal posture of submission), it is a government-provided opportunity to experience the indignity in its fullest and most complete form. And it keeps me open to future opportunities to ameliorate these conditions.

This is, in its own way, non-violent resistance (though I wouldn’t actually compare the issue to civil rights.) In the words of Martin Luther King, “The goal is not to defeat or humiliate the opponent but rather to win him or her over to understanding new ways to create cooperation and community.” Only when we acknowledge what is not working and commit to finding new solutions will those solutions appear.