Teaching film in Dadaab

After editing a film in Dadaab, I spent two and a half weeks teaching film as part of FilmAid’s Participatory Video Project. Ordinarily the PVP curriculum consists of individual units focused on different aspects of filmmaking, to form about a year’s curriculum. Our class was a general one, though, where I tried to teach a group of 12 students everything about filmmaking. We lost a few days at the start of the class, so we had to condense about 60 hours of work into 13 days.

In my mind, this is the most important work that FilmAid does. Our large screenings are very public, visually stunning, and do provide the community with useful information. But these trainings are designed to change lives in a focused way. Ideally (and we are moving towards this goal) the PVP program turns out a large group of filmmakers empowered to tell stories on a par with any other film school in the world. The training was also the most meaningful part of my time here, as I really got to know my students personally.

Training a class is in many ways like training an army. Yes making film is lots of fun, but the students I am teaching are also becoming warriors. Their films are weapons and they are fighting against oppression, for knowledge and understanding.

I decided to focus my time on conceptual teaching and “soft skills” of filmmaking, discussing abstract concepts such as composing shots and introducing characters. (I am indebted to Rob Milazzo, a former film teacher, for some of the style and techniques I used.) Because the hard skills of using a camera can be learned gradually through discovery, I believed the transfer of knowledge and discussion of higher elements of filmmaking was more important. I wanted to instill in the students a feeling of the power they had as storytellers, that even in a documentary they were constantly choosing and responsible for every element of every frame.

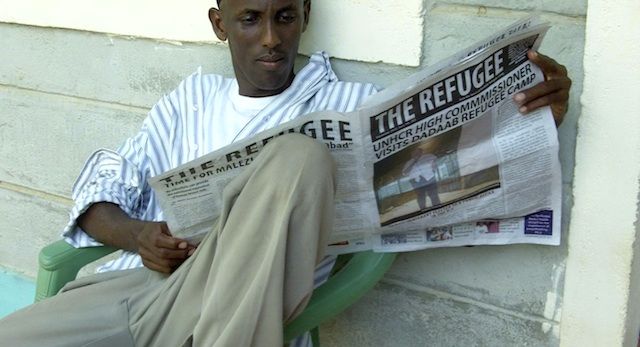

We began with shot composition, where I showed them several dramatic newspaper photos. We discussed the symbolism of different elements, the use of composition, color, and choosing a background. We discussed different ways the subject could have been photographed and what they would mean. We watched film examples, including a few from “The Graduate” and a fight scene in the desert from “Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon.” (the best question about the fight scene: “why are they fighting with swords? Why don’t they use guns?”) Then we moved on to character introductions, discussing the different ways characters can be introduced. “Taxi Driver” and “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” were two examples used.

Most of the class chose to use themselves in our character introduction exercise. They got up to the front of the classroom to discuss their lives, and then we discussed as a class how to best portray the life events. One student described the bombing of his village, the loss of his family, and his journey alone across hundreds of miles. I was stunned, and could not even process the words coming out of my own mouth as I asked him whether he would portray this through interview or action, what shot sizes he would use.

It was hard to tell the results of this theoretical approach; the Somali- and Ethiopian-speaking students often had a hard time understanding what I was saying, and for cultural reasons were not telling me when they didn’t understand something. It worried me that some seemed far more engaged after the two-hour lesson on using the camera than in all the theoretical discussions. One student told me “thanks Mr. Michael, we learned so much today!” “What about when we discussed Scorcese?!” I wanted to reply.

This is why I was pleasantly shocked when we did our first sample interviews. Not only were they for the most part brilliantly shot and executed, but they did literally everything I had asked. When prompted as to why they had chosen a particular camera angle, for the most part they had deep motivations.

Their own footage was the best teachable lesson. “What have you included in this frame?” I asked one group, pointing to the corner of the frame. “There is our subject and their house.” “What else?” They could not see anything else in the frame. “There is a giant ‘USA’ in the center of your frame,” I exclaimed, pointing to the USA material used to construct their subjects’ house. “Did you want that there?” They laughed, and I repeated, “you are responsible for every single thing in your frame.” That was when it really sunk in.

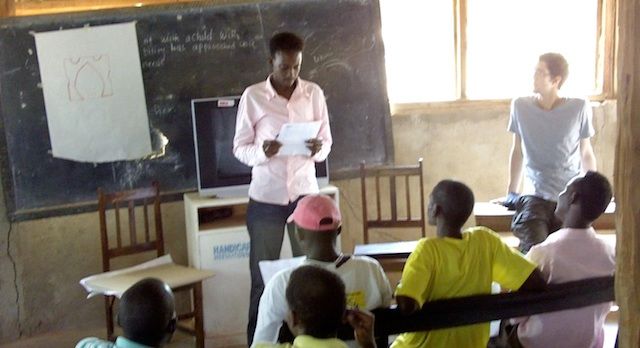

For their final projects, four-minute character introductions, they chose to work with Handicap International, a group that advocates for disabled peoples’ rights and spreads land mine awareness. Of the three subjects for the three videos, one was a blind man, another a parapalegic woman, and the third a schoolteacher. They shot the films over three days, and we had the last four days to edit.

My students’ biggest request was that they be taught Final Cut Pro; not having access to laptops, they had no opportunity to learn editing, and this seriously impacted their abilities as filmmakers. (Personally I cannot understand how anyone who has not edited a film is in a position to make one.) My admittedly ambitious goal was to teach them editing and have them edit the projects themselves in only four days, with only two computers. (In fact, they *had* to edit themselves, because two of the films were in Somali!

The first day of editing started three hours late due to logistical issues. I was nervous about our ability to accomplish our task in the time we had. We set up outdoors with a long extension cord connecting the laptops and external hard drives. They fought the glare with their eyes to see what was on the screen as I showed them the basics of Final Cut Pro.

I believe in teaching the real thing and not dumbed-down solutions like iMovie. The first hour was immensely frustrating, as some of them struggled to learn how to use a mouse at the same time as grasp advanced subjects such as the Final Cut Pro timeline. But once these concepts are grasped FCP is very intuitive to use, and so the challenge was only to fight the frustration along the learning curve. Lo and behold, within (I am not joking) 1.5 hours, all but a few students knew how to edit on Final Cut Pro. I never expected this.

For expediency, I then assigned the best editor from each group to work with the team to assemble a rough cut. They already had log sheets of every shot, so they found their clips easily. As they worked, I continued to show them more advanced techniques and tools whenever they seemed ready.

The rough cuts were between 12-16 minutes, and I told them to make them four minutes. With about five hours left to go of our total editing time, one group responded by deleting all their work and starting over. I was shocked but had thankfully saved a backup copy during lunch; we began working together to cut it down.

The last day, I took the editing desk and pared each group’s project down, asking them what was being said in Somali and questioning everything that did not seem necessary to the story. They saw how tight it was possible to make the edit and seemed to learn from watching me as well.

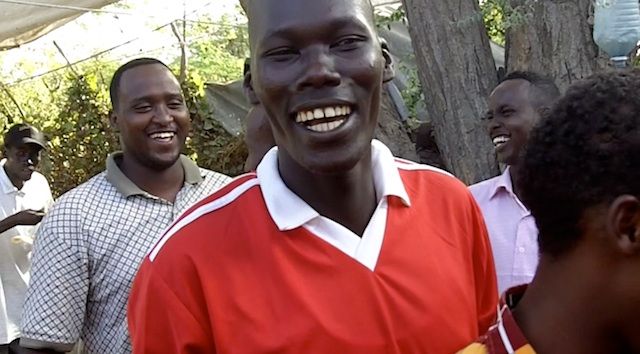

I spent a sleepless night spent polishing the edits and adding credits, and we finished the class with a viewing of the films. Dawit arranged an amazing party in the Ethiopian section of the camp, complete with an Ethiopian coffee ritual and delicious Injera.

I left by a bumpy 6-hour car ride the next day, satisfied and thoroughly exhausted, the completed films sitting on my hard drive.