Day one in Kakuma

Our new Executive Director and board just took a trip to Kenya, and it brought me back to the first time I visited Kakuma. I hear that some of the refugees recorded a video message for me and am excited to see it. “It will make you go kkkkk,” they said, which is Somali-text for lol. I can’t wait!

My field experience in Kenya was to conclude with a week in Kakuma, a camp in the North of Kenya that used to house primarily Sudanese refugees until the situation in that country stabilized a bit. It now holds thousands of Somalis as UNHCR struggles to deal with the flood of refugees fleeing that country.

My trip began haphazardly. You see, there are two modes in what I’d call Kenya Time: the see-what-happens-oh-well mode, which involved not really leaving much time for things and just hoping for the best, and the oh-crap-we-have-to-be-there-on-time mode, which involves leaving literally half a day for things that might take five minutes, to anticipate things like traffic jams, arrests, broken cars, dead cell phones, etc.

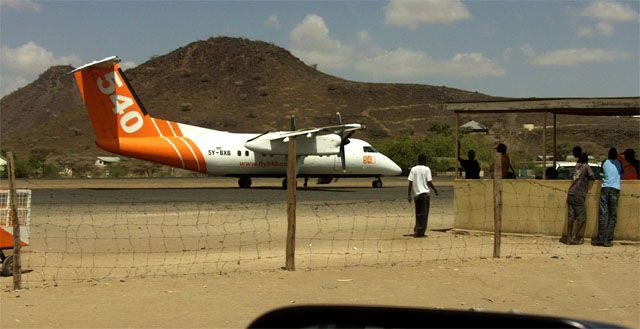

My first attempt, on a Monday, was on see-what-happens-oh-well time. I left for the airport 45 minutes before the time I was supposed to board the plane. I confidently asked for Jomo Kenyatta airport (that was the only airport name I knew,) and when we arrived said “oh no, we have to go to the back. The part where the private airplanes take off from.” There was no back, and we soon found out it was Wilson airport we were looking for. Oops. On Wednesday I left for the airport five hours before my flight was supposed to depart and had a good three hours of waiting in the terminal – much better. (Plus, I knew the name of the airport that time!)

Upon exiting the plane I was immediately overwhelmed. The Turkana region, where Kakuma is located, is a starkly beautiful desert area that reminded me of a cross between Southern California and Sedona, Arizona. Conical mountains, perfect domes of huts, acacia trees and dried-up riverbeds punctuated miles of desert expanse. I did not notice, or chose to ignore, impoverished people with no shoes looking at us in our car with a quiet desperation.

My happiness grew when I arrived at the FilmAid office. A cohesive group with smiles on their faces welcomed me, including Kate, my friend from Nairobi. Tony, the Program Manager, held a meeting where we went around in a circle and each of us said where we were from and what we were doing.

We drove to what was to be my first night screening in a giant truck. Filled with boisterous camaraderie, I stared eyes agape at a blood orange sunset washing the camp. These people have jackets, shoes! They were driving motorcycles, looked well-fed! It was not the desperate desolation that had cut a memory into me in Dadaab.

At the screening, I spoke to Andrew, who told me he was a lost boy from Sudan and knew Valentino Achak Deng from “What is the What” and had still not found a copy of the book to read. He told me his story – how he lost his family, trekked alone with other boys across the Sudan; how he was supposed to go to the US with the other Lost Boys but couldn’t because the 9/11 bombings happened. He said “I’m 28 years old. If I were in your country I would have had several degrees by now. I want to be a journalist and here I am doing nothing.”

And it came crashing down. That veneer of joy, the kids who as we spoke were dancing around us to the pre-show reggae, the sunset that was still spewing bits of purple into a starry sky. A fucking deceit. And I looked at this alien world with new eyes, looked at the beauty through a screen of sadness.

The screening was a supreme event. We got on top of the truck and threw a screen down, set up a projector, and blasted some tunes to attract the dancing kids. Then we showed this huge audience some cartoons and several films about womens’ rights.

On our drive home the exhaustion of the days’ travel was setting in and I barely had the energy to speak. I tucked my malaria net into the corners of my bed and just eked out enough energy to set my alarm before I fell to the bed.